Hurling

Irish Sport 1950-2000, An Insight into Irish Sporting Success, ed. Ian Foster, Manticore , 2002, pp 26-49

The Rules

Hurling is a field game played between two teams of fifteen players each. The players line out as follows: a goalkeeper, three full-backs, three half-backs, two centrefield players, three half-forwards and three full-forwards.

The two fundamental requirements for the game are a hurley or caman and a ball or sliothar. The Irish word for hurley - caman, recognises its nature by incorporating the Irish word for crooked - cam. And that is what a hurley literally is, a crooked stick, made from ash wood, about 13 centimetres wide at the striking point and 75 centimetres long. Ash has always been regarded as the ideal wood for the making of hurleys because the timber has a pliability that is necessary to withstand the impact of two hurleys coming in contact with one another. The sliothar or ball weighs about 120 grams and has a diameter of about 7.6 centimetres. It contains a core of cork, covered in layers of thread and cased in pigskin leather. The thread around the cork is very important as it prevents the cork breaking up. If this were to happen the ball's pressure would be reduced and its resilience suffer. The leather casing is held togther by wax stitching and coated in a water-resistent protection.

A game of hurling lasts for 70 minutes, divided into equal halves with an interval of 15 minutes. The length of the playing surface is 150 metres and the width 75 metres. each end of the field are two goal posts with a crossbar approximately 2.15 metres high. The aim of the game is to get the ball between the goalposts. When the ball goes under the crossbar it is a goal and when it goes over it is a point. One goal equals three points.

If a player puts the ball over his end line wide of the posts, a 65 metre free is awarded to the opposing team. When a player puts the ball over the sideline, a free strike from the sideline is granted to his opponent in which the sliothar has to be struck from the ground .

Frees are awarded for picking the ball off the ground with the hand, for carrying the ball too far in the hand, for pushing the opponent in the back, for holding an opponent and or rough and dangerous play. All frees are taken by rising the ball with the hurley and striking it without catching it in the hand. In normal play it is permitted to catch the ball in the hand from the air or raise it to the hand from the ground with the hurley. Each team is allowed five substitutes during the course of the game.

The referee has six officials to help him control the game. At each set of goalposts there are two umpires, one to decide on goals and a second on points. When a goal is scored, a green flag is waved and a white flag is waved in the event of a point. As well, there are two linesmen who decide which side has put the ball over the sideline and to award the free shot to the other side.

The game demands a degree of courage. To the uninitiated, it can appear dangerous but to properly trained players it is not. Anyone brought up with the game learns to defend himself instinctively and protect himself with the hurley. The most common injuries are skinned knuckles, or cuts and bruises to the head. It is a very fast game with the ball moving from end to end of the field at a great pace. It can be a very exciting game when the ball is moving fast and the players are well-trained in the skills of the game. A variation of hurling called Camogie, with slightly different rules, is played by women.

Gaelic Athletic Association

The relationship between the Gaelic Athletic Association and other sports has not always been good but since 1971, an amicable working relationship with most sporting bodies has been established. Trevor West, in his book The Bold Collegians, says, 'The GAA ban prohibiting members of the association from playing in, or watching, "foreign" games was formally revoked in 1971. Given the links, in 1884, of the Protestant athletic establishment with unionism and of the GAA with nationalism, some such dichotomy was probably inevitable; the tragedy is that the ban so long outlasted the conditions that gave rise to it'.

Michael Cusack founded the GAA in 1884 with the purpose of encouraging the Gaelic games; Cusack was an excellent club cricketer and rugby player and favoured all sports. It was the second generation of GAA administrators, in the 1890s, that developed 'the ban' mentality.

Hurling

The first mention of hurling in Ireland is a literary reference dated 1272 BC By the 18th century hurling had grown in popularity and that century is sometimes called 'the golden age of hurling'. During this time it was patronised by landlords, who sponsored teams and organised games for wagers with neighbouring landlords. However, by the 19th century, hurling had begun to decline in popularity; the French revolution created an atmosphere of uncertainty -landlords withdrew their patronage, the Catholic Church frowned on Sunday games, the middle class disassociated themselves from many forms of popular culture and the Great Famine (1846-49) had its influence too.

By 1880 the game was in a perilous state. As one authority stated, hurling could 'now be said to be not only dead and buried but in several localities to be entirely forgotten and unknown .. .'but in 1884 Michael Cusack founded the Gaelic Athletic Association and it set out to restore Gaelic pastimes, athletics, hurling, football and handball. The GAA was successful in its ambition and today hurling is the third most common game in Ireland.

By 1950 hurling was well administered with a clear set of rules and organised with competitions for different age levels. The ambition of every player is to be a senior player, be picked for his county and win an All-Ireland final. This is achieved by playing for a county and winning the intercounty competition of his province, Ulster, Munster, Leinster or Connacht. The four champion counties from each province then play the All-Ireland semi-finals with the winners contesting the All-Ireland final. The final is played at Croke Park, Dublin on the second Sunday of September. In 1954,80,000 watched the All-Ireland final. In the early part of the last century attendances were small but in the 1920s 30,000, in the 1930s 50,000 and 1940s, 60,000 were common attendance figures. More recently numbers have declined below the 1954 crowd asimproved facilities were developed which reduced capacity, and health and safety requirements had to be met. At the present time Croke Park is being developed and, when it is completed, will have a capacity of 80,000.

The Gaelic Athletic Association was more than a sporting organisation; it also had a cultural dimension as it became involved in the revival of the Irish language, Irish dancing and other aspects of Irish culture. There was a political dimension in that it identified with the separatist wing of the Nationalist Ireland movement. Michael Cusack, although a keen supporter and player of the Anglicised games, saw them as a threat to the development of the national game, but Archbishop Croke of Cashel, who was the patron of the association influenced for a moderate view. However in 1904, written into the GAA rule book was the following: ‘Any member of the Association who plays or encourages in any way rugby, football, hockey or any imported game which is calculated to injuriously affect our National Pastimes, is suspended from the Association'. The rule was to remain on the books until 1971.

A related rule was Rule 21, which prohibited members of the Royal Irish Constabulary (later, the Royal Ulster Constabulary) and British defence forces from participating in Gaelic games. It also forbade GAA members from attending social functions hosted by the RUC or British forces. This rule was revoked at a special congress of the GAA at the end of 2001.

By 1950 Tipperary (14 wins), Cork (16 wins) and Kilkenny (13 wins) had established themselves as the strongest hurling teams. London, in 1901, caused a major surprise when they won the final, and Dublin won the All-Ireland final six times before 1938. Geographically, the game established itself in the south-east and in an irregular swathe westward across Ireland, and in isolated pockets such as North Kerry, the Glens of Antrim and the Ards Peninsula in County Down.

The winning team in the All-Ireland senior hurling championship receives the MacCarthy Cup. It was presented to the GAA in 1922 by William, later more commonly known as Liam MacCarthy. He was the first treasurer of the London County Board of the GAA, which was formed in 1896, and later president. He was also involved in the Gaelic League. A man of great character, proud of his Irish roots, he is regarded among his compatriots as the ‘Father of the London GAA’. He died in 1928 and is buried in Dulwich cemetery, London. The cup was first presented to Bob McConkey, captain of the victorious Limerick team in 1922.

Michael Collins, Paddy Dunphy and Harry Boland at a hurling final in Croke Park circa 1920. Later Collins and Boland were to take opposite sides in the Civil War.

During the first half of the century the game produced many fine players, who became heroes to their clubs and their counties and were feared by opponents. One of the greatest was Cork player, Christy Ring (1920-1979), who played in ten All-Ireland finals, winning eight of them. He captained three of the winning teams. He was the outstanding forward in the game, playing at senior county level from 1939-1962. Another outstanding player was Mick Mackey, Limerick (1912-1982). His best position was centre half-forward and his achievements with his club, Ahane, and Limerick are legendary. His senior playing career stretched from 1930-1947.

By the middle of the 20th century the Gaelic Athletic Association had established itself very firmly in the mind of the Irish people. It was one of the integral parts of Irish society and culture, together with the political party of De Valera, Fianna Fail, and the Catholic Church. At a time of economic misery and large-scale emigration, the GAA provided an opportunity for people to express themselves and celebrate sporting achievements. Hurling was a major outlet.

Cork, (12 wins), Kilkenny (13 wins), Tipperary (10 wins) in the period 1950 to 2000 have continued to dominate the All-Ireland finals but Waterford, Limerick, Galway, Offaly and Clare have also achieved success.

The early '50s were dominated by Tipperary-Cork rivalry. Tipperary won the All-Irelands in 1949, 1950 and 1951 after many breathtaking encounters with their old rivals. Cork duly came along in the following three years and captured the three titles after equally enthralling contests with the men from Tipperary. These. encounters took place within the framework of the Munster championship but such was the dominance of Munster hurling at the time, that in all the six years, the Munster champions went on to claim All-Ireland honours.

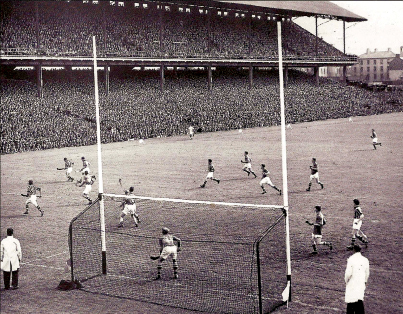

1950 All-Ireland Final. Tipperary beat Kilkenny 1-9 to 1-8 before 68,599 spectators. Jimmy Langton [Kilkenny, No 12) threatens the Tipperary goal.

A halt was put to this dominance in the middle of the century by the men of Wexford. This county was originally a football stronghold and its hurling prospects at the beginning of the decade were anything but promising. There was gradual improvement and they reached the AlI Ireland final against Cork in 1954. A record number of people for a hurling final, 84,856 saw Cork victorious in an epic game. The winners were captained by the inimitable Christy Ring but the Wexford side had their collosi in the three Rackard brothers, Nicky, who played full-forward, Billy, who played centre-back and Bobbie, who played cornerback. Wexford came back in the following two years to win All-Irelands and they won a third in 1960.

Brendan Fullam in his book Giants of the Ash describes one of Bobbie Rackard's greatest games. The moment of greatness came for Bobbie Rackard in the 1954 All-Ireland final against Cork. With about 20 minutes remaining, Nick O'Donnell, the great Wexford full-back, broke his collar-bone and had to leave the field. Wexford reshuffled their team and took Bobbie Rackard to full-back. He proceeded to give a power-packed and impeccable display of defensive hurling that will forever have a special place in hurling history and will be talked about whenever great feats of individual brilliance are recalled.

1955 All-Ireland Final. Dr Kinane the Archbishop of Cashel and Patron of the GAA throws in the ball to start the final between Wexford and Galway. This had been the practice since 1884 but ceased in the 1970s; from then on, the only players present for the throw-in are those at centrefield.

The Wexford teams were immensely popular with the public and this was shown in the huge numbers who came to see them play. In the 1955 final against Galway, 72,854 spectators turned up, the eighth largest attendance at an All-Ireland. In the National League final against Tipperary in May 1956, the attendance of 45,902 constitutes a record. The record for a hurling All-Ireland was set in 1954 and the second largest crowd attended the 1956 final, when 83,091 saw Wexford defeat Cork. The fourth and fifth biggest crowds were present in 1960, when Wexford beat Tipperary, and in 1962, when Tipperary reversed the result.

Wexford had something special to offer. Physically they were big men but allied to their size was a high level of skill. They were noted sportsmen, renowned for performances that sometimes approached chivalry. Many of them revealed qualities of leadership that set them apart from the rank and file of humanity: there was a romance, an energy and an excitement about them that made them larger than life; they appeared to step out of the pages of the heroic past of myths and legends. Many hurlers have ballads and tributes written of them. One of the finest to be written was on the death of Nicky Rackard, the chorus of which said:

We watched you on September's fields

And lightning was the drive

You were the one Cuchulainn's son

In nineteen-fifiy-five.

One of the contributing factors for the increased popularity of hurling was the radio. Radio Eireann, the national broadcasting station, may not have been a very exciting media experience during the fifties, but its one claim to fame was the coverage of Gaelic games. In this it was fortunate in having one of the most popular broadcasters of all time, Michael O'Hehir. Beginning in 1938 he soon established himself as an outstanding broadcaster. He had distinctive voice, a great knowledge of the game and was an intimate acquaintance of the players and the little-known villages and townslands they came from. On Sunday afternoons his voice was to be heard in kitchens and living rooms, in pubs and shops, in public parks and on beaches bringing his exciting account of a Munster or Leinster final or All-Ireland day to people far and near. His voice was also carried to Irish emigrants abroad through radio link-ups. He gave remote places a national platform and made unknown players household names. When television arrived he transferred successfully to it but he will always be remembered as the radio broadcaster who could paint a picture of the game and make it live as vividly as if one were present.

Towards the end of the '50s another team came on the scene to challenge for hurling honours. Waterford made their first breakthrough to All-Ireland glory in 1948, when a star-studded team defeated Dublin in the All-Ireland. The success was greeted by a welcoming-home crowd of 25,000 people and six bands. Waterford didn't capitalise on the victory and failed to qualify for an All-Ireland again until 1957, when they were beaten by Kilkenny, who were returning to glory after ten years in the wilderness.

Waterford got their revenge in 1959 when they came through Munster and qualified for the All Ireland against Kilkenny. The game attracted a crowd of over 73,000 and was rated one of the greatest finals ever; a tense and thrilling contest played at a furious pace. For a long time it appeared to be going Waterford's way, and they led by five points at the interval, but Kilkenny came back to snatch a draw. The replay attracted nearly 78,000. Waterford had learned most from the drawn game and, after another superb encounter, victory went their way by 3-12 to 1-10. There were some marvellous displays for Waterford from their captain, Frankie Walsh, and their centre-forward, Tom Cheasty. A big, strong player and a most unorthodox striker of the ball, his forte was cutting through the centre, making straight for the goal and palming the ball over the bar.

30th June 1957. The Munster semi-final between Cork and Tipperary at Limerick which Cork won by 5-2 to1-11. In the second half Christy Ring went off with a broken wrist. Mick Mackey. who was doing umpire for referee Mick Hayes of Clare, says something to Christy Ring as he leaves the field.

The sides met for a third time in seven years in the 1963 All-Ireland. Waterford shocked Tipperary in the Munster final and Kilkenny defeated Wexford in Leinster. The game was a record-breaker in that the combined scores created new figures for a 60-minute final, Kilkenny 4-17, Waterford 6-8. The Kilkenny victory was due to some outstanding displays, from Eddie Keher, who scored fourteen points in the game, and Seamus Cleere, who played a captain's part.

The '50s will also be remembered for the Railway Cup competition, the interprovincial competition, which began in 1926. It reached the height of its popularity during this decade and the final, which was always played at Croke Park on St Patrick's Day, used to attract over 40,000 people. The competition gave countrywide exposure to great players from less successful hurling counties who otherwise had little chance of national exposure. Players like Jimmy Smyth of Clare and Jobber McGrath of Westmeath come quickly to mind. At the same time it gave better-known players the opportunity to show off their brilliance. The competition was dominated by Christy Ring for over two decades during which he won an incredible eighteen finals with Munster! For a host of reasons the Railway Cup began to decline in popularity in the late seventies and, even though it is still played, it is but a shadow of its former self

The 1960s were dominated by Tipperary. Of the ten All-Irelands between 1960-1969, the county played in seven, winning four and losing three. The team was regarded as the greatest that ever wore the blue and gold. It began to show its potential when winning the 1958 AlI Ireland, beating Galway after accounting for Kilkenny in the semi-final. Its progress was halted when unexpectedly beaten by Wexford in the 1960 All-Ireland. The defeat was attributed to fatigue after an extremely strenuous encounter with Cork in that year's Munster final.

Success came in 1961 when Dublin were defeated in the final. What was expected to be a relatively easy encounter turned out to be an extremely difficult battle. Dublin nearly surprised everyone by snatching victory and might have done so but for the sending off of Lar Foley in the second half and the saving of a certain goal by Tipperary goalkeeper Donal O'Brien. The defeat was a misfortune from which Dublin never recovered. They were badly beaten in the following year's Leinster championship and have never since reached an All-Ireland final.

In contrast Tipperary went on to more victories. They defeated Wexford by 3-10 to 2-11 in a thrilling encounter in the 1962 All-Ireland, which saw outstanding displays from Donal O'Brien, John Doyle, Tony Wall, Tom Ryan and 'Mackey' McKenna for Tipperary, as well Tom Neville, Pat Nolan, Phil Wilson and Ned Wheeler of Wexford. Tipperary set their sights on a third in a row in 1963 but they were halted in their tracks by Waterford in the Munster championship. However, they came back the following year to take the Munster championship, defeating Cork by 3-13 to 1-5 and the All-Ireland by defeating Kilkenny by 5-13 to 2-8. They were to repeat the success in 1965, crushing Cork by 4-11 to 0-5 in the Munster final, and defeating Wexford by 2-16 to 0-10 in the All-Ireland.

The Tipperary team of 1964-65 is generally regarded as one of the greatest hurling forces that ever took the field. Traditionally Tipperary teams had shone in their back players but this team also had a fluent attack. Every one of the forwards was a match-winner in his own right. With Jimmy Doyle and 'Babs' Keating on the wings, Donie Nealon and Sean McLoughlin in the corners, and Larry Kiely and Mackey McKenna providing the backbone, Tipperary had a forward line that was unrivalled in its brilliance. At the other end of the field, John O'Donoghue between the posts received magnificent cover from John Doyle, Michael Maher and Kieran Carey. John Doyle won his eighth All-Ireland in 1965, bringing him equal to Christy Ring with the record of having won the greatest number of All-Irelands on the field of play. Further out Mick Burns, Tony Wall, Michael Murphy in 1964 and Len Gaynor in 1965, were outstanding and the team was completed by Theo English and Mick Roche in the centre of the field. Even the best of teams reach a peak. This seems to have happened to Tipperary in 1965. A chink appeared in their mantle of invincibility in 1966 when they lost the National League 'home' final to Kilkenny. This was more than a mere defeat. It was a huge psychological victory for the Kilkenny men, their first defeat of Tipperary in major competition since 1922!

After the league defeat, Tipperary made a few changes for the championship. It was expected they would be forewarned but they didn't learn anything in either physical or mental readiness. Their opponents, Limerick, showed themselves a team of fire and dash and Tipperary just couldn't cope with their super-fitness and were well-beaten, 4-12 to 2-9. Unfortunately Limerick were unable to capitalise on their significant victory and were beaten by Cork in the Munster semi-final. Cork went on to beat Waterford in the final. Kilkenny were Cork's opponents in the All-Ireland final and were widely tipped to win but they were out-hurled and out-manoeuvered on the day and were beaten by 3-9 to 1-10. Cork were greatly helped by a quartet of splendid players from the under-21 side, three McCarthys, Gerald, Charlie and Justin, and Seanie Barry. It was twelve years since Cork had won an All-Ireland and there were unprecedented scenes of joy when the final whistle sounded.

If Tipperary were poor in 1966 they had a brilliant Munster campaign in 1967. They pushed Waterford, who had put Cork out of the championship in the first found, aside in the semi-final and Clare in the final. Tipperary's opponents in the All-Ireland were Kilkenny. On a blustery day Tipperary had the breeze in their favour in the first half and led by double scores at half-time. But, they were totally eclipsed by Kilkenny after the interval and lost by 3-8 to 2-7.

It was a disappointing result for John Doyle who was going for his ninth All-Ireland. It was his last year to play for Tipperary. For 19 seasons between 1949 and 1967 he had played senior hurling for his county. During these years he had never failed to turn out in a championship game and he never retired injured during a game. Starting at left cornerback, his career got a new lease of life in 1958 when he lined out at left-wing back, and he finished his hurling days at right cornerback. He played in ten All-Irelands and won eight of them. He also holds the record for National League victories, 11 in all. His ability and his longevity at the top were recognised when he received a decisive vote for the left cornerback position in the 1984 Team of the Century and the 2000 An Post Millennium Team.

John Doyle, winner of eight All-Ireland senior hurling championship medals in a career, stretching from 1949 to 1967 is acclaimed by Tipperary supporters.

A namesake of his, Jimmy, was one of the most brilliant forwards of the period. Playing thirteen All-Irelands between 1954 and 1971, he won nine of them. Four of them were in minor finals of which he won three, in 1955, 1956 and 1957. At the senior level he played in nine finals, winning six. He captained the minor team to victory in 1957, and the senior team in 1962 and 1965. He was also picked on the teams of the century and the millennium.

In his article on Jimmy Doyle in Hurling Giants, Brendan Fullam had this to say: 'Among the great thrills of his early days was to hear a man shout "Congratulations" to him as he walked back to school with his bag on his back. "What for?" said Jimmy and the reply was "You have been selected on the Munster Railway Cup team." He travelled to Belfast accompanied by Christy Ring. Coming off the train Ring donned a cap and pulled it down over his eyes. Jimmy was a bit baffled and asked Ring why he was wearing the cap in that manner. ''Ah'', said Christy, "I don't want to be recognised." There were occasions when Ring liked privacy and as time passed Jimmy was to learn and understand for himself the significance of Ring's feelings. Even to this day there are times when Jimmy wishes he could operate incognito.'

As well as John Doyle, Kieran Carey, Tony Wall and Theo English had disappeared from the hurling scene when Tipperary faced into the 1968 championship. They had an easy victory over Cork in the Munster final and came up against Wexford in the All-Ireland. Wexford trailed by 1-11 to 1-3 at the interval but staged a great rally in the second half. Inspired by newcomers Tony Doran, Tom Neville and John Quigley, plus a great half-back line of Vinny Staples, Dan Quigley and Willie Murphy, they transformed the interval deficit into a final victory score of 5-8 to 3-12. It was a sad day for Tipperary captain, Michael Roche, who was captaining his team to a second All-Ireland defeat. Tipperary's greatest period of hurling dominance came to an end with this defeat. There was to be one brief flash of brilliance in 1971 before the county settled down to a long spell in the hurling wilderness. After the riches of the '50s and '60s, the famine of the '70s and '80s was difficult for the county's supporters to bear, and when it came to an end in 1989 there were unprecedented scenes of joy and euphoria throughout the county.

Cork and Kilkenny reigned supreme in the 1970s. The best way to view the period 1969-79 is via the statistics. 22 teams contested the eleven All-Irelands during the period. Kilkenny appeared in eight finals, five times as winners. Cork had six appearances, four of them victorious. Wexford made three unsuccessful appearances and Galway made two. Limerick had one success and one failure, and Tipperary made one successful appearance. So, between them, Kilkenny and Cork won nine of the eleven All-Irelands. Another feature of their supremacy is the way they dominated their respective provincial championships. Kilkenny won the Leinster championship eight times during the period, including five in a row from 1971-75. Cork also won eight Munster championships at the same time and their successes included a five in a row from 1975 to 1979.

Cork defeated Tipperary in three major competitions during 1969, a year that probably marks the turning point in Munster hurling from Tipperary dominance of the 1960s to Cork supremacy of the 1970s. Cork defeated Tipperary in the Munster final, their first championship success over this opposition in 12 years. In the All-Ireland against Kilkenny, although the game was even enough in the first half, Cork appeared to have the edge. After the interval Kilkenny put in a storming performance and ended up easy winners by 2-15 to 2-9.

In 1970 the playing time for provincial finals and All-Ireland semi-finals and finals was increased to 80 from 60 minutes for all senior championship games. It was to remain so until 1975, when the 75 minute final was introduced and this has been the duration of finals in these competitions since.

Another development was the re-introduction of All-Ireland semi-finals. They were played until 1958 after which Galway made their debut in the Munster championship. Up to then Galway, as representatives of Connaght, used to meet the Leinster or Munster champions in rotation, in the All-Ireland semi-final. From 1970 onwards, Galway played in the All-Ireland semi-final.

Cork came out of Munster after an exciting game with Tipperary in the 1970 Munster championship. In Leinster, Wexford surprised Kilkenny, who were without Eddie Keher for most of the game. They defeated Galway in the All-Ireland semi-final and played Cork in the final. It was a poor game of bad temper and rough play at the end of which Cork had a 14 point margin of victory on a scoreline of 6-21 to 5-10.

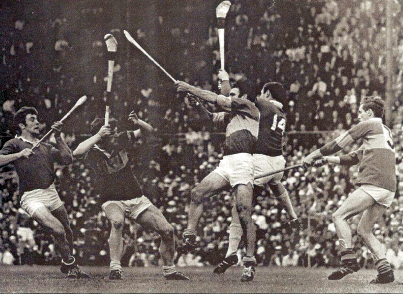

Cork v Tipperary in a Munster championship game, circa 1970

Limerick were the form team going into the 1971 Munster championship, having beaten Tipperary in the National League final. In the Munster semi-final they recorded their first championship win in 31 years over Cork. In the Munster final they came up against Tipperary at Killarney and lost by a point in a thriller. In Leinster, Kilkenny were back in the winning frame again and defeated Wexford in the final. Tipperary accounted for Galway in the AlI-Ireland semi-final. The final was the first to be televised in colour and it attracted the smallest attendance for a final since 1958. In an epic tussle Tipperary came out on top winning by 5-17 to 5-14.

The All-Star scheme was introduced in 1971. Under this scheme the top 15 players of the year were chosen by a committee of sports journalists and GAA officials and were given a trip to the USA. The intention behind the trip was to encourage and promote the organisation and playing of hurling among Irish exiles across America. A sponsor was required and the Irish tobacco company, P. J. Carroll and Co., came on board. They remained as sponsors until 1979, when Bank of Ireland took over. Powerscreen International took over in 1994 and they were succeeded by Eircell in 1997. There have been a number of changes in the scheme over the years and foreign trips have become rarer. The award of an All-Star remains the ambition of most hurlers.

Kilkenny were rank outsiders against Cork in the 1972 All-Ireland. Cork, who defeated Tipperary in the Munster semi-final replay, had the easiest of victories against Clare in the final. Kilkenny defeated Wexford in a replayed Leinster final and accounted for Galway in the All-Ireland semifinal. It was expected that the 80 minute All-Ireland would suit the younger Cork side but it was the older and more experienced Kilkenny players who were the sprightliest at the finish. Cork led by eight points with 22 minutes remaining but Kilkenny scored 2-9, without reply from Cork, and transformed the eight point deficit into a seven point lead with a score of 3-24 to 5-11.

Limerick's turn eventually arrived in 1973. They had been threatening since 1971 and they made it through Munster with victories over Clare and Tipperary. Their opponents were Kilkenny,who defeated Wexford in the Leinster final. It was the first time since 1940 that Kilkenny and Limerick met in an All-Ireland final. Kilkenny were handicapped by injuries and Limerick won their first All-Ireland in 33 years.

Limerick came through Munster again in 1974, beating Clare in the final. The Leinster final between Kilkenny and Wexford was one of the most fantastic matches ever seen at Croke Park, with Kilkenny victorious by 6-13 to 2-24. They beat Galway in the All-Ireland semi-final and came up against Limerick in the final. In a repeat of the previous year, Kilkenny were never under pressure and won convincingly by 3-19 to 1-13. Eddie Keher scored 1-11 for the winners and Pat Henderson gave an inspired performance at centre-back.

Eddie Keher was one of the all-time great hurling forwards. His senior career spanned the period from 1959-1977 during which time he played in 11 finals, winning six. He also won nine Railway Cup medals and three National Leagues. After the All-Star system was introduced in 1971, he won five awards. He probably scored more than any other forward in the game, including 2 goals and 11 points in the 1971 All-Ireland final, which makes him the second highest scorer on record. His name fits comfortably in the company of Christy Ring, Mick Mackey, Nicky Rackard and Jimmy Doyle. In an interview with Brendan Fullam in Giants of the Ash Eddie Keher said: 'I enjoy everything about the game, watching, playing, training, practising. Whereas All-Irelands are the glamorous occasions, some of my greatest memories are from club championship or tournament games. I suppose "firsts" are inclined to be memories, and my first school, county medal in 1952 (under 14) is high on the list. My first appearance with Kilkenny in 1959, my first win, 1963, captain of a winning team in 1959; my first and only county championship with Rower Inistioge in 1968 - all have their own significance. 1972 against Cork was probably the best 80 minutes of hurling I have had the pleasure of playing in.'

The big surprise in the 1975 championship was the defeat of Cork, who accounted for Limerick in the Munster final, by Galway in the All-Ireland semi-final. It was Galway's first time to qualify for the All-Ireland since 1958. Their success against Cork was anticipated by their victory over Tipperary in the National League final, their first victory in this competition in 24 years. They were expected to do well against Kilkenny, who defeated Wexford in the Leinster final, but their performance on the day was a complete disappointment and they lost to Kilkenny by 2-22 to 2-10.

Cork won three titles in a row in 1976, 1977 and 1978. They beat Limerick in the 1976 Munster final and came up against Wexford, who trounced Kilkenny in the Leinster final and beat Galway in a replayed All-Ireland semi-final. In an even contest Cork came out victorious in the end, by 2-21 to 4-11, as a result of some well-taken points by Jimmy Barry Murphy. The same two teams qualified for the 1977 All-Ireland. Cork came through Munster with victories over Waterford and Clare. During the latter game there was an armed robbery of £24,000 of the day's takings from under the stand at Thurles. Cork defeated Galway in the All-Ireland semi-final. Wexford successfully defended their Leinster title, defeating Kilkenny in the final. This was Eddie Keher's last championship game for Kilkenny. Cork gave a great display in the final with Denis Coughlan and Gerald McCarthy particularly outstanding and won by 1-17 to 3-8 for Wexford, who never really played up to expectations.

In 1978 Cork made it three in a row when they beat Kilkenny by four points in the All-Ireland final. Cork again defeated Clare in the Munster final while Kilkenny overcame Wexford by a goal in a thrilling Leinster final. The Leinster men defeated Galway in the All-Ireland semi-final.The final was expected to be a classic but it didn't fulfil its promise and Cork were in front by 1-15 to 2-8 at the final whistle. Cork won their fifth Munster final in a row in 1979 at Thurles when they beat a disappointing Limerick who were without Pat Hartigan their star player. They looked good for a fourth All-Ireland in a row but their plans came unstuck against Galway in the All-Ireland semi-final. Kilkenny were Galway's opponents in the All-Ireland, having defeated Wexford in another exciting Leinster final. The Connacht men had considerable expectations but they failed to deliver on the day and were beaten by 2-12 to 1-8. It was Kilkenny's 21st title.

One of the outstanding developments of the 1970s was the introduction of a senior club championship. The club, based on the parish and with strong family loyalties, has always been the backbone of the Gaelic Athletic Association. In the very early years of the Association, the club represented the county in the All-Ireland championship. In the course of time it was allowed to include players from the rest of the county and the team gradually evolved into a representative county side. In 1970 it was decided to start a new championship for the club teams which won their respective county titles. The club championship was born and it has gone from strength to strength. It is played late in the year with the final taking place on St Patrick's Day and it gives an excitement and purpose to the clubs involved at a time of year when the other championships have been completed. It generates as much interest and enthusiasm as the Railway Cup competition used to do in its heyday. Its strength lies in the way it has levelled the playing pitch somewhat, giving clubs from weaker counties a chance of achieving greatness.

The last two decades of the 20th century saw the arrival of three new teams as contenders for All-Ireland honours. Galway, who had a lone All-Ireland senior championship to their credit, dating back to 1923, became a force in hurling and captured three titles. Offaly, whose previous achievement was confined to two junior titles in 1923 and 1929, broke through the psychological and traditional barriers to win senior championships for the first time. Clare had a lone AlI-Ireland dating back to 1914 and they overcame decades of sickening defeats when they won two All-Irelands in the nineties and established themselves as meaningful members of the hurling establishment. Galway's victory in the 1980 All-Ireland was received with tremendous enthusiasm, not only in Galway but much further afield. The estimated 30,000 supporters who greeted the team in Eyre Square were probably more enthusiastic and emotional than any crowd that came out anywhere in Ireland to welcome home an All-Ireland side. The wait had been so long and the disappointments so many that the crowd wallowed in the joy and pride of it all.

During the previous decade there were signs that Galway hurling was turning a corner. There were still upsets and disappointments, as in the 1975 and 1979 All-Irelands, but they were important straws in the wind. Galway were now managed by Cyril Farrell, one of the new brand of managers who were making names for themselves on more and more county teams. In the All-Ireland semi-final, Galway played Offaly, who had won their first ever Leinster senior title with a victory over Kilkenny, and won by two points. In the Munster final, Galway came up against Limerick, who upset the odds when beating Cork who were going for their sixth successive Munster title,. The pairing of Galway and Limerick in the All-Ireland was unique. Limerick were favourites on the basis of their league performance and their defeat of Cork in the Munster championship. They also had one of the best forward lines in the game with Eamon Cregan, Joe McKenna and Ollie O'Connor on the inside line. On the day Limerick failed to produce their best form and Galway did to win by 2-15 to 3-9. Backboning the Galway team in the historic victory of 1980, were the Connolly brothers, John, Michael and Joe, with Padraic as a sub. In fact seven brothers were on the Castlegar team that won the All-Ireland club championship in 1980. In a piece he wrote for Brendan Fullam, in Giants of the Ash, John described how the family bonded: 'It was also a tradition of ours,even after us getting married with our own homes, we would all meet in our old home place the morning of a match, known to everybody in Galway as Mamo's, which was an old name for Grandmother. We would chat about the game, and without realising it, we built up a kind of spirit that stood to us on the field. Then as we left Mamo's she would shake the bottle of holy water on us, saying: "Mind yourselves and don't be fighting, and don't come back here if ye lose". Of course we had many a fight and we lost plenty of times, but we were always welcomed home.' .

It was to be Offaly's turn in 1981. They defeated Wexford in the Leinster final. Limerick came out of Munster but lost the All-Ireland semi-final to Galway after a replay. They were dogged by misfortune and injury and despite their defeat, won many friends for the tremendous courage and tenacity shown in the face of misfortune. Galway were undoubtedly favourites for the AlI Ireland and looked even more so at half-time with a comfortable lead. But Offaly refused to buckle, gradually reduced the lead and snatched victory from the jaws of defeat with a great goal by Johnny O'Flaherty about five minutes from time.

Kilkenny were back in the frame in 1982 and 1983. They defeated Offaly in the Leinster final as a result of a controversial goal and Galway in the All-Ireland semi-final. Their opponents in the final were Cork, who had come through Munster with ease, defeating Waterford in the final. Kilkenny were devastating, defeating Cork by 3-18 to 1-13, with the man of the match award going to Christy Heffernan, who scored 2-3 for the winners. Kilkenny created a record for the county in 1983, when they won the league and the championship for the second year in a row. They beat Offaly in an exciting Leinster final and came up against Cork in the AlI Ireland for the second year in a row. Cork scored an easy victory over Waterford in the Munster final and had a comprehensive victory over Galway in the All-Ireland semi-final. The final was a disappointment, marred by a strong wind, and, although there were only two points between the sides in the end, Kilkenny were never really in danger. For Kilkenny goalkeeper, Noel Skehan, the victory brought a record ninth All-Ireland senior medal. Although the number is greater than that won by Christy Ring and John Doyle, it does not carry the same distinction as three of them - 1963, 1967 and 1969 - were won as a sub to Ollie Walsh. The remaining six were won on the field of play in 1972 (as captain), 1974,1975, 1979, 1982, 1983.

The year 1984 was the centenary year of the founding of the Gaelic Athletic Association at Thurles and it was decided to play the All-Ireland final in the town. Offaly and Cork qualified for the final. Offaly won in Leinster as a result of beating Wexford in the final. Cork won out in Munster following a dramatic victory over Tipperary in the final. For the first time since 1954 there were two All-Ireland semi-finals, with Antrim representing Ulster, where hurling is very much a minority sport. Offaly defeated Galway and Cork defeated Antrim in the semi-finals. The final was a major disappointment as Offaly played way below form and were beaten by 3-16 to 1-12 by Cork.

Offaly were very disappointed with their performance but came back to win the 1985 All Ireland. They had an easy victory over Laois in the Leinster final. Cork came through in Munster, beating Tipperary in the final, but were shocked by Galway in the All-Ireland semifinal. Galway were favourites as a result but in a closely contested final, they were beaten by Offaly on a scoreline of 2-11 to 1-12.

Offaly failed to get out of Leinster in 1986 as they were defeated by Kilkenny in the Leinster final. Cork came out of Munster after victory over Clare in the final. Kilkenny were well-beaten by Galway in the All-Ireland semi-final and Cork were nearly shocked by Antrim. Galway were favourites for the final but the tactics which proved successful against Kilkenny, backfired against Cork, and they were beaten by 4-13 to 2-15.

It was a case of third time lucky for Galway in 1987. In Leinster, Kilkenny were victorious after a brilliant contest with affaly. Tipperary won out in Munster for the first time since 1971 after an epic tussle with Cork, which went to a replay and extra time. Galway defeated Tipperary in the All-Ireland semi-final, which attracted the biggest crowd, over 49,000, since the semi-final in 1958. Kilkenny defeated Antrim after a struggle. The All-Ireland was a tough game played in a tense atmosphere and Galway were victorious by 1-12 to 0-9 for Kilkenny. Galway made it two in a row in 1988, beating Tipperary in the All-Ireland. Tipperary defeated Cork in the Munster final and Offaly defeated Wexford in Leinster. Galway defeated Offaly and Tipperary defeated Antrim in the All-Ireland semi-finals. The final was a much publicised affair as each team was managed by high profile managers, Galway by Cyril Farrell and Tipperary by Babs Keating. In the end victory went to Galway by 1-15 to 0-14.

The advent of team managers was one of the developments of the '80s. There had always been managers, or at least spokesmen for bands of selectors, but the '80s saw the rise of a new phenomenon, the arrival of the manager with a higher profile than any of the players. In many cases a former outstanding player, who was given almost complete control over the preparation of his team. He became the sole spokesperson for the players. He made all the decisions on the field and was given a distinctive bib, which identified him as he paced the sidelines during a game. In many cases he was well paid, was attributed God-like genius in the event of his team's victory and resigned when they were defeated. He was the centre of the media's attention and his every utterance quoted. His arrival signalled a growing professionalism in the preparation of teams.

Tipperary made it back to the winner's enclosure in 1989 against such unlikely opponents as Antrim. The latter beat Offaly, who carne out of Leinster, sensationally in the All-Ireland semi-final. In the other semi-final, Tipperary, who won in Munster for the third year in a row, beat Galway in a tense game. Antrim were really no match for Tipperary in the final, which saw the winner's star forward, Nicky English, establish a scoring record for an All-Ireland hurling final of 2 goals and 12 points.

Cork deprived Tipperary of four in a row in Munster in 1990. Offaly won out in Leinster but were beaten by Galway in the All-Ireland semi-final. Cork won the other semi-final against Antrim. Galway were favourites for the final but in a thrilling contest Cork came out on top to win by 5-15 to 2-21.

Tipperary came back to take the 1991 All-Ireland. They came out of Munster after a couple of epic games with Cork. Kilkenny won out in Leinster and qualified for the All-Ireland with victory over Antrim in the All-Ireland semi-final. Tipperary defeated Galway in the other semi final and went on to defeat Kilkenny in the final.

An action shot from the 1991 All Ireland semi-final between Tipperary and Galway

Kilkenny won in 1992 and 1993 defeating Cork and Galway respectively. In 1994, Offaly came back in dramatic fashion to snatch victory from defeat. Their opponents were Limerick, who scored a comprehensive victory over Clare in the Munster final. Offaly were five points down wlith as many minutes to go but, in a dramatic turn of events, they scored 11 points during the period to win by six points from a hapless Limerick side.

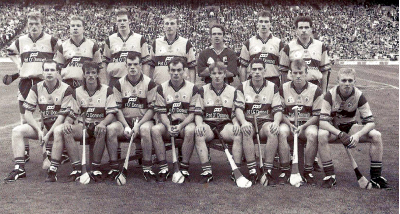

Clare came through in dramatic fashion in 1995. They had given warning the previous year when they beat Tipperary, reversing an 18 point drubbing by the same side in 1993. They beat Cork in the Munster semi-final and Limerick in the final at Thurles. The scenes of joy after this victory were unbelievable. Motivated and driven by a committed manager, Ger Loughnane, the team went all the way, beating Galway in the All-Ireland semi-final and Offaly in the final. Thus the cup returned to Munster and Leinster's recent apparent dominance was halted. Clare brought a new dimension to the game. They reached new heights of physical fitness, psyched themselves up with convictions of certainty and were led by a Messiah-like figure in Loughnane who inspired them with a blinding purpose. Above all the team included some of the most exciting players to appear on the scene for a long time and they served up a brand of direct, skilful and aggressive hurling, which swept opponents off their feet.

1995 The Clare senior hurling team that made the breakthrough to win their first All-Ireland since 1914.

Back row: Brian Lohan, Michael O'Halloran, Frank Lohan, Conor Clancy, David Fitzgerald, Sean McMahon, Ger O'Loughlin.

Front row: Liam Doyle, PJ. O'Connell, Ollie Baker, Anthony Daly, James O'Connor, Fergal Hegarty, Fergus Tuohy, Stephen McNamara.

Ger Loughnane was Millennium Manager of the Century at the end of 2000. It was a major award and an indication of his gigantic stature in the history of managers. An outstanding player in his own right, he was a member of the Munster Railway Cup team for seven years in a row from 1975 onwards. His playing years spanned 16 years at senior county level. The Clare team of the period was an exceptional team that probably never got the reward it deserved - an AlI Ireland title. Two National League titles were won in 1977 and 1978. The failure to win an All Ireland must have rankled with Loughnane and must have been the dominating motivation when he took over as manager of Clare in 1994. The team had not won an All-Ireland in 80 years. Brendan Fullam in Legends of the Ash describes his success: 'His exuberance and infectious tenthusiasm spilled over onto the players. His approach, befitting his teaching profession, was hortative. He urged and encouraged; he praised and drove. He was a generator of confidence, a moulder of spirit. A man of unshakeable faith in the potential of his panel and players, he imbued in them a deep pride in the jersey they wore, in the county they represented, in the game they played. He bred the winning mentality.'

If Clare were responsible for the excitement of 1995 it was Wexford that brought out the colour and excitement of 1996. Inspired by their impressive manager Liam Griffin, they swept through Leinster, defeated Galway in the All-Ireland semi-final and Offaly in the final. As with Clare this Wexford victory gave hurling a new lease of life, brought out the supporters in their thousands, blanketed the stadia with masses of colour and made it great to be alive. Clare were back again in 1997, beating Tipperary in the Munster final and the same opposition in the All-Ireland final. This came about as the result of a change in the running of the All-Ireland series. Under the new scheme the beaten finalists in Leinster and Munster entered the All-Ireland series, meeting the winners in Ulster and Connacht at the quarter-final stage. This system had an unexpected result in 1998 when Offaly, beaten in the Leinster final, went on to beat their Leinster conquerors, Kilkenny, in the All-Ireland final. This year saw the re-emergence of Waterford as a force in Munster hurling. It was hoped the county could deliver on its promise as the arrival of new teams or the re-emergence of old ones give a great fillip to the game and increases its support.

Cork were back in winning mode in the 1999 All-Ireland, beating Kilkenny in the final. In the year 2000, after losing two years in a row, Kilkenny came back to take the All-Ireland title in no uncertain terms with a comprehensive victory over Offaly in the final. The latter team had sensationally defeated Cork in the semi-final. One of the stars of the Kilkenny team was DJ Carey, one of the most exciting players in the game at the end of the second Millennium. An outstanding forward he illustrates all the skills of hurling with a brilliant turn of speed.

At the beginning of the third Millennium the game of hurling is in a reasonably strong position. The support for the game at intercounty level is stronger than ever. The televising of all the major games over the summer months has given it increased exposure and attracted more followers. The training of teams has become more and more important and counties are spending enormous sums of money preparing teams for the championship. The demands on players and the sacrifices they must make are very strenuous. More and more players are looking for rewards for their labours and this is where the question of professionalism arises. At the moment it would seem that players are not interested in hurling as a professional game but would like to get more generous expenses for their commitment. Whether this will lead to professionalism or semi-professionalism down the line remains to be seen.